My Translation of Sappho's Hymn to Aphrodite

with thoughts on Sappho, Erotic Magic, & the Sacred Power of Sex

Why Sappho? Why Now?

I had other plans for this week—most notably, finishing part 2 of my commentary on the Hymn to the Moon—but Aphrodite did not approve. On the day of Her ingress into Pisces (the sign in which she is traditionally said to “exult”), She muscled her way in, gently but firmly, to let me know that I needed to prioritize getting this Hymn to Aphrodite out to the wider public.

Here’s what that looked like: Yesterday (!) I was seated working on editing the audio version of my commentary on the Moon when without any forethought, I sort of dazedly switched screens, opened this page, and began writing this essay. It wasn’t until I was a few paragraphs in that I realized I had changed tasks and was doing something entirely unplanned.

When I stopped and came to my senses, I quickly recognized one of the goddess’ signature moves. She works gently, but with a power to enrapture that blots out my oh-so-rational plans and leaves me putty in Her hands. Sigh. So much for my commentary on the Moon this weekend.

On the bright side, and perhaps especially appropriately for Venus in Pisces—the planet of creativity and pleasure in a watery, dreamy sign—the prose just flowed. So here is your unplanned gift from Aphrodite to celebrate her exaltation in Pisces. Because if anyone ever knew how to exult (and be exulted by) Aphrodite, it’s Sappho.

Sappho & Eros

I’m not going to go into a whole biography of Sappho here. Others have done that pretty well. I’ll simply say that she wrote (and practically invented) lyric poetry in the 7th c. BCE, on the Greek island of Lesbos, and that she is probably most famous for writing poetry about her love for girls—hence giving English the word “lesbian.” (If you’re interested more generally in the subject of female-female love in ancient Greece, this article is a great starting point.)

But to many poets throughout the millennia, Sappho is quite simply the sexiest poet ever. (#Sorrynotsorry, Romantic poets!) To wit:

To read Sappho in the original Greek is to experience language physically, in your body. Words like “erotic” or “sensual” are woefully overused, but they’ll have to do. She’s not even terribly explicit by modern standards. And yet…. and yet. Her poems manage to be simultaneously delicate, silky, tinkling, effervescent, and intoxicating, while also thundering out a command that brings you to your knees.

When Sappho says “come,” you come. And when she says “go,” or when (even worse) the poetry fragment cuts off mid-sentence, you beg for more.

This is not an accident.

Sappho’s genius is the creation of poetic form that not only invokes the subject of Aphrodite (either the goddess Herself, or the love that She rules over), but also in its choice of words and rhythm, creates an erotic response in the body.

There are many fine translations of Sappho’s work (my favorite being Anne Carson). But when I first read Sappho in the Greek, I couldn’t believe how unabashedly sexy the Greek was in comparison to the existing English translations, which always seemed to err on the side of the most decorous (read: vanilla) word choices possible.

So that’s what I’ve tried to do here with my translation of this, Sappho’s most famous complete poem—a Hymn to Aphrodite. I’ve tried to capture the sexiness of the poem in the original Greek. I’ve used blank verse because that’s my preferred form for Greek translations. And I’ve tried to stay faithful imagery, intensity, and eroticism of the Greek by using contemporary language. I wouldn’t say my translations are the best, because Sappho is far too complex for any translation to be sufficient in and of itself. But I do think my translations do what I want them to do, which is capture the immediacy of the feeling of reading Sappho in the original.

Sappho & Ancient Erotic Magic

One thing that I think becomes apparent in my translation is the magical quality of this poem, which uses the language of ancient Greek love spells. Others have written on this topic extensively, but for our purposes, we can note these two main ways in which Sappho deploys magical language and imagery in this poem:

As a Hymn to Aphrodite, it uses rather strong conjuring and summoning language to direct the goddess’ attention to the petitioner (Sappho herself), get Her to appear, and then request a special favor from Her. In this way, the Hymn is somewhat reminiscent of later theurgical spells that compel a god to take up residence in a particular location (usually a statue or temple). It’s not quite compulsory (presumably Aphrodite could refuse to appear), but it certainly comes close.

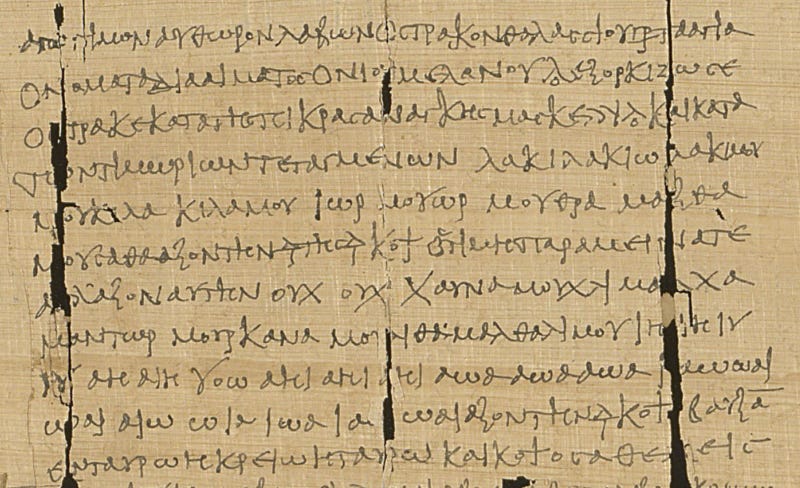

Within the Hymn, the voice of Aphrodite Herself uses the language of ancient Greek “binding” spells (of the sort found in the Greek Magical Papyri) to ensure that Sappho will get her desired girl. The use of this type of binding magic flies in the face of our modern notions of consent, since it strives to magically compel your object of desire to have sex with you even against their will. We have literally hundreds of such erotic binding spells from antiquity, including some between two women, so scholars are quite sure that Sappho’s verses here are, in fact, using magical language.

For me, the magical language in this poem “hits different” (as the kids say) because, like desire itself, it is a tangled knot of feeling. On the one hand, we have Sappho compelling Aphrodite to come down and compel a girl to fall in love with the poet.

But at the same time, there’s another erotic relationship at play in the poem—the relationship between Sappho and Aphrodite themselves. And that relationship is characterized by a tender, playful tone that is more reminiscent of bedroom talk than it is of what we moderns conventionally associate with “prayer.”

And this, for me, is the magic of Sappho: Her poems testify to a time when Love, Desire, and the Sacred were intwined in an intimate embrace. When a Goddess could be in love with a Woman, and vice-versa, and the two of them might set off in pursuit of a third girl—all in the name of Divine Love. Which is not separate from human sex.

I’m certainly not the first person to notice all this, but I do think my translation makes the small contribution of giving English readers a sense of the feeling of reading the Hymn in the Ancient Greek. I hope you find it inspiring.

With the love of the stars,

Kristin

Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite

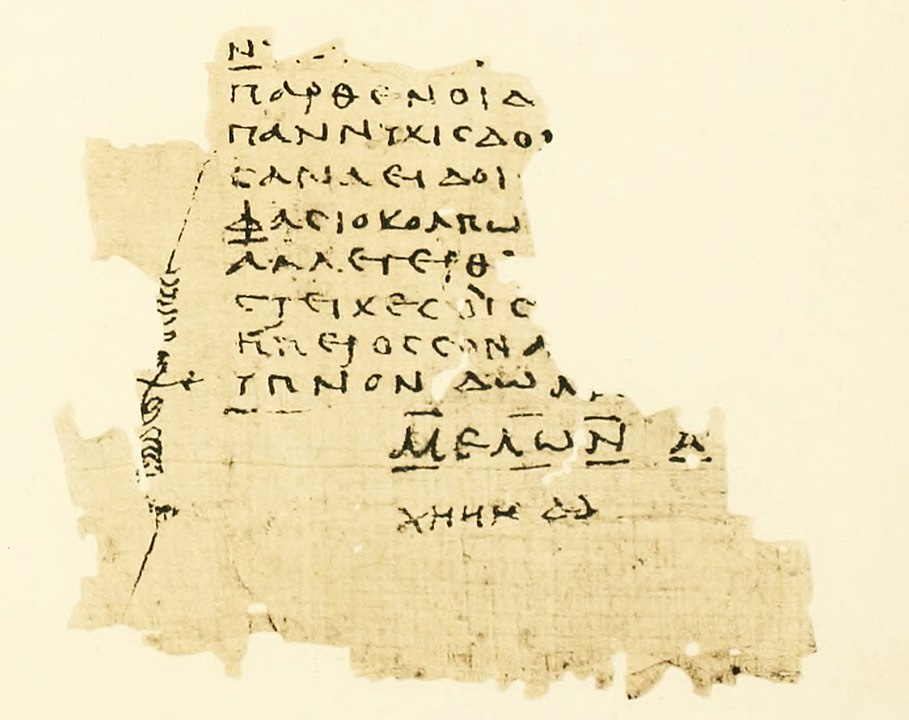

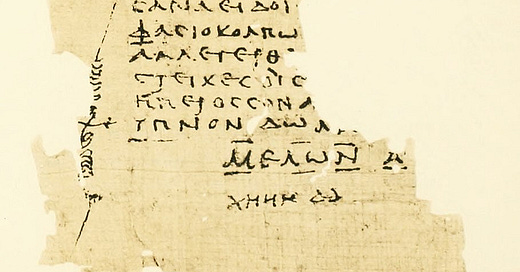

(Sappho, Fragment 1)

Dapple-minded deathless Aphrodite

Child of a trickster god: I beg you,

don’t vanquish my heart

with anguish and grief, my Lady.

Time and again you’ve

heard my voice from afar,

quit your father’s golden house,

and come to me.

You yoked your chariot, and

swift, noble sparrows

spiraled you down

over the dark earth,

a thick whorl of wings

from heaven through the ether

until—suddenly—

you were on me.

Blessed one! With that deathless

face of yours, you chuckled

and inquired why, yet again, I suffered.

Why, yet again, I summoned.

And what I wished you’d work

in my frenzied breast:

Whom should I cajole?

Whom should I draw

into your love play?

Come on, Sappho—

who’s wounded you?

Because whoever flees,

will turn and give chase.

And whoever won’t give it up,

will suddenly grant everything.

And whoever doesn’t love you now,

oh, they’ll love you all right—

whatever their will.

You came to me before, Aprhodite.

Come again now.

Break me free from my tortures.

Glut my heart with its desires.

Do it! You, yourself—

be my comrade in arms.

A Note on Sparrows:

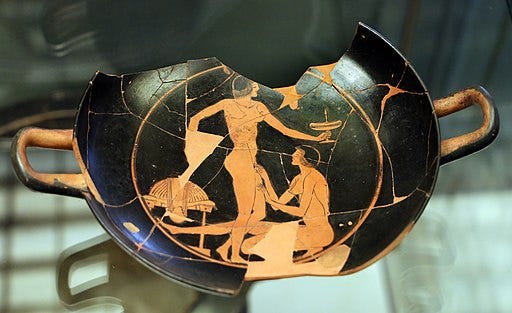

Traditionally, Aphrodite was often depicted as riding in a chariot drawn by a flock of sparrows. These birds were considered symbols of almost profligate sexuality and reproduction—sort of how many English-speakers stereotypically view rabbits.

If you’d like to immerse yourself in some Venusian ASMR, here’s a flock of sparrows chirping and beating their “whorl of wings” in a bucolic Polish village.

Truly beautiful rendition. The level of intimacy you conjur in the mind is exquisite. You can feel the very pulse of APHROGENIA!

wow, incredible <3 <3 <3