To say that Pluto is a complicated figure is (prepare for dad-joke-worthy pun) quite an understatement.

In fact, there is so much to cover when speaking of the Underworld and its Lord that I’ve divided it up into two posts:

This free essay, which covers how the Orphic Hymns understand (and map) the cosmos, including how they depict the underworld and Pluto, and

The translation of the Hymn proper, along with extensive (EXTENSIVE!) commentary and charts detailing the major esoteric astrological and Mystery meanings hidden in the Greek text. That post is available to paid subscribers. (And don’t worry…if you sign up for a paid subscription after the email goes out later today, you can access the translation on the Mysteria Mundi substack home page.)

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that though I’ll refer to the famous myth of Pluto and Persephone in each of these posts, I’ll reserve my more extensive commentary on that story for my eventual translation of the Hymn to Persephone.

So let’s dive in.

Part 1: “Fractal Animism” & the Limits of Either/Or Thinking

In order to understand the Orphic descriptions of Pluto, we need to take a BIG step back to contemplate how the Orphics understood the cosmos as a whole. This is important because we’ve all-too-often been fed a view of the Greek cosmos that is based on ideas of hierarchy, binaries, and top-down emanation.

But that’s not how the Orphic Hymns roll. Orphic thinking about the cosmos tends to follow a pattern of what I call “fractal animism.”*

Let’s take each part of this phrase “fractal animism” separately.

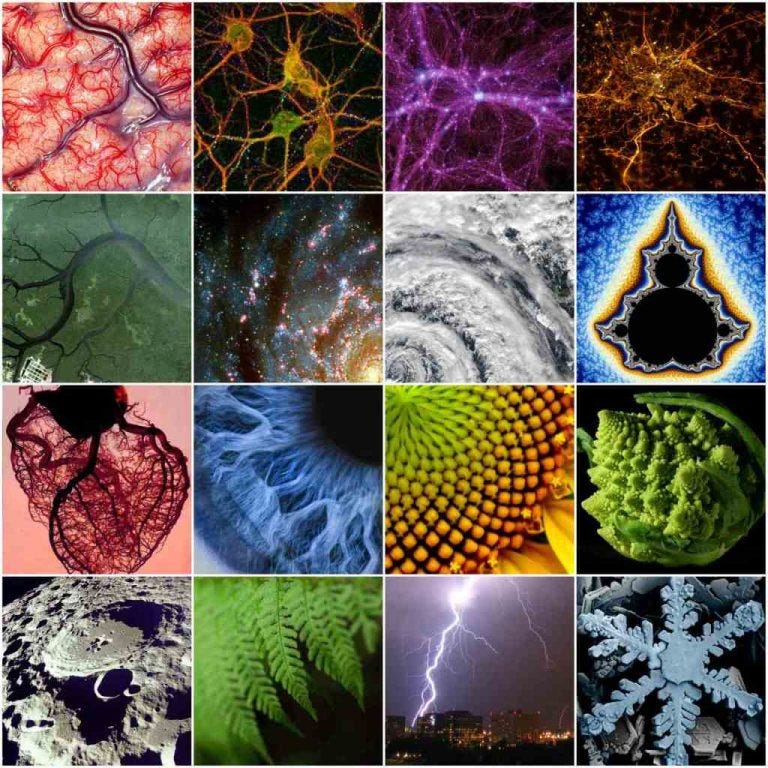

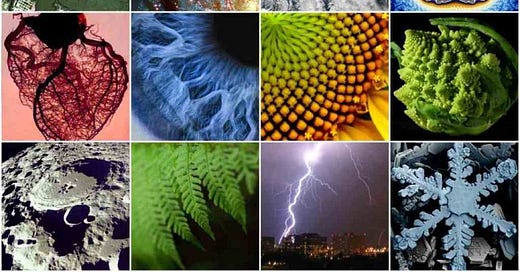

We can call Orphic cosmology “fractal,” because the Orphic understanding of the universe describes (and values) repeated patterns at different scales across a single organism. Examples of natural fractals include branching patterns in lightning, trees, or our lungs; the sworls of certain algae; a snowflake; the leaves of a fern.

Here’s what Orphic fractals are NOT: They are not top-down. They are not “as above so below.” They are not “the Real” vs. “reflection of Reality.” **

Orphic fractals are polycentric, often rhizomatic structures that not only repeat themselves, but are reversible/invertable, able to be observed and understood from different angles.

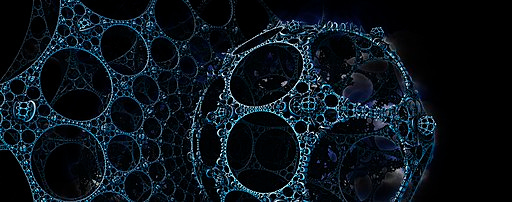

Let’s do a little thought experiment that can help us visualize the Orphic cosmos:

Picture a polyhedron that you can rotate and observe from different angles. Which face is the “original” one, and which faces are the copies? The question doesn’t even make sense. Even more bewilderingly, how would you decide which corner of the polyhedron is “highest?”

Trick questions, of course. The answer is all are, or none. Or whichever one you choose to look at in a given moment.

That’s how Orphic “fractals” work. There’s not one “original” or “higher” side to a snowflake. And there’s not one “original” or “higher” side to the cosmos. There are simply different faces we can examine one at a time.

Now let’s take a look at that second term: “animism.” It’s a somewhat clumsy word, but it does what we want it to do, which is indicate that for the Orphics, every element of the cosmos, every fractal pattern is always alive. Which is to say, embodied.

In the Orphic Hymns, humans, plants, animals, and even minerals are alive and have bodies. Planets, too, are alive and have bodies. And gods. And stars. And natural phenomena that we cannot see, such as the winds, or natural laws, or even (as I wrote about in my intro to the Hymn to Kronos) space-time itself.

Some of these living bodies are like ours—flesh and blood—and others are more subtle, as is the case with plants, or clouds, or starlight. But there is nothing at all in the cosmos that is not a living body of some sort.

So let’s continue our polyhedron meditation a bit further. Imagine that the polyhedron is alive. It breathes. It has innards. When you look at each of its sides, a different face winks out at you. You can’t look at them all at once, but you can examine them one at a time in order to form a sense of the whole.

Then imagine a network of hundreds, thousands, even millions of these little living, breathing polyhedra strung out into bigger patterns. Perhaps they are stacked together to make one giant polyhedron. Perhaps they are strung end-to-end to make a long chain. Perhaps they are thrown into patterns that look random, but upon inspection, you realize that each pattern contains some variation of these little winking polyhedra.

THAT’s what the Orphic cosmos is like.

Part II: Pluto as Living Fractal

By now, it should be very obvious that the elementary school version of Greek myth where Zeus is King of Olympus, and all the other gods are arrayed at His feet is not how the Orphic ancestors actually understood the cosmos.

For the ancient Orphics, Hades, or the site of the Underworld, was fractally related to everything above-ground. We tend to read our modern notions of “above and below” as hierarchical (with above representing primacy, “the good,” etc.). But for the ancients, Pluto is a fractal image of Zeus.

No hierarchy implied, no primacy, nor are they even actually separate at a fundamental level. Mythically, this relationship is expressed by saying Zeus and Pluto are brothers.

Fundamentally, Zeus and Pluto are simply repeating patterns or faces of the same living Being. And that Being has a primary purpose to liberate and sow Life.

Zeus/Jupiter accomplishes this act of liberation and life through his body of light, visible in lightning, the planet Jupiter, seeds and sperm, and other phenomena associated with abundant life-generation. As such, Zeus is understood as the ruler of the daytime cosmos, seated in the heavens above the Earth (aka Mt. Olympus in myth). We see a fractal variant of Zeus’ life-generating power every time we look at the Sun, who draws plants upwards towards its light.

Pluto, on the other hand, accomplishes this same mission of liberating and sowing life, but He does so through His body of shadows or shade. And for Orphics, Pluto’s realm was just as necessary to the generation of life and liberty as Zeus.’

On a very literal level, anyone who has ever labored under the hot sun knows that shade, like light, is absolutely necessary for life to flourish. Shade grants us respite from the unwearying and parching effects of strong light and heat. When we’re in the shade, we take a sip of lemonade or cold water, wipe our foreheads, and feel our strength renewed. It allows us a moment to recollect ourselves, to stand back and survey what we’ve done so far and chart our next steps.

That’s exactly what Pluto does in the Orphic cosmos: He shelters, renews, and refreshes. We see this in the Hymn on several levels from the literal to the mythic to the astronomical to the esoteric. Let’s look each one of them in turn.

The Great Composter

Let’s start with the literal. As farmers, the Greeks were well-aware of the life-giving properties of compost, and how dead plant, animal, and even human material contribute to abundant harvests. ***

In the Orphic Hymn to Pluto, we see this very literal understanding of the life-giving properties of Pluto in lines that refer to him as greasy or oily, reminiscent of blood. He harvests bodies indiscriminately and composts them. His realm, therefore, is said to be responsible for the annual earthly bounty that sustains all beings.

We can see why Pluto is traditionally understood as He who rules the parts of the earth that are beneath the surface topsoil—everything from the deeper layers of composted rhizomatic/mycelial growth to subterranean cave systems, to the the magma layers that would erupt periodically from active volcanoes throughout the Mediterranean, creating layers of dark black fertile soil. Without the cycle of death, there would be nothing to fertilize and nourish life. (It’s interesting to note that volcanoes are particularly active in the areas that birthed Orphism—Southern Italy and Sicily.)

So far so good…but there’s more.

The Great Abductor

We all know the myth of Pluto’s abduction of Persephone, and have been told how it describes the turning of the seasons. The common interpretation is that when Pluto abducts Persephone, Demeter’s grief causes plant life to dry up and disappear, thereby producing Winter; when Persephone reappears in Spring, Demeter’s rejoicing causes the flowers to bloom.

But there’s a paradox here: when Pluto abducts Persephone in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, it is Springtime. Meaning that during the Spring and Summer, Persephone is in the underworld, not up on land.

Essentially, what we have here is another face of the fractal. From one viewpoint—that of visible phenomena such as flowers and agricultural growth—Demeter’s cycle of grief and rejoicing precipitates the seasons. The flowers bloom because Demeter wishes to commemorate Persephone’s return.

However, from the point of view of Pluto—that is, of the invisible under-earth life generation that happens in the shadows—Springtime happens because in abducting Persephone, Pluto has put Her life-force to work under the earth, pushing the plants and flowers up from below. And when She returns to the earth’s surface in Autumn, that underground life-force stops working and everything dries up.

Again, this is not a question of either Demeter or Pluto causing the seasons to change. It is both/and.

The Great Liberator

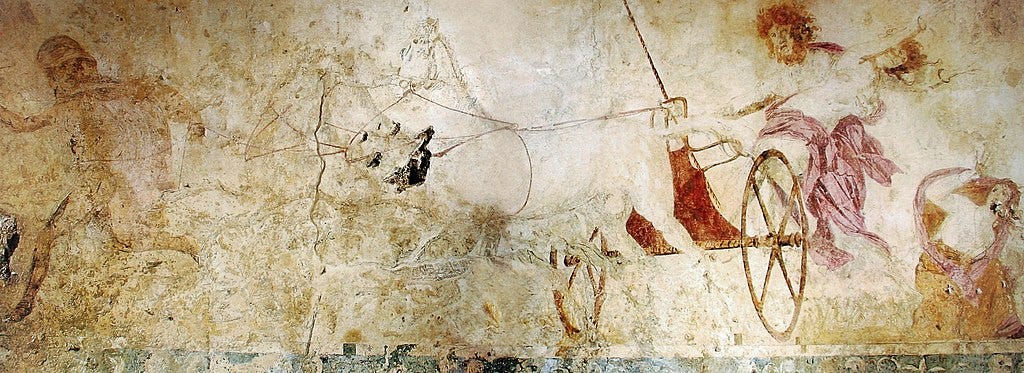

Hold on to your esoteric hats, though, because there’s even more to the myth of Persephone’s abduction than an explanation of the seasons. The abduction myth is also a description of the human soul journey: Ask not for whom Pluto’s chariot rolls, gentle reader. It rolls for thee.

For we will all succumb one day, often suddenly, to the Great Abductor. Not a single one of us will escape being dragged to Pluto’s kingdom. And when we get to that kingdom, the Orphics believed, we will have the chance to pause, reflect, and remember our role in the grand scheme of things. In the shade, beside one of Hades’ refreshing streams, we might remember that we are, fundamentally, of the same family as Earth and Starry Sky, and that our true home is in the Heavens.

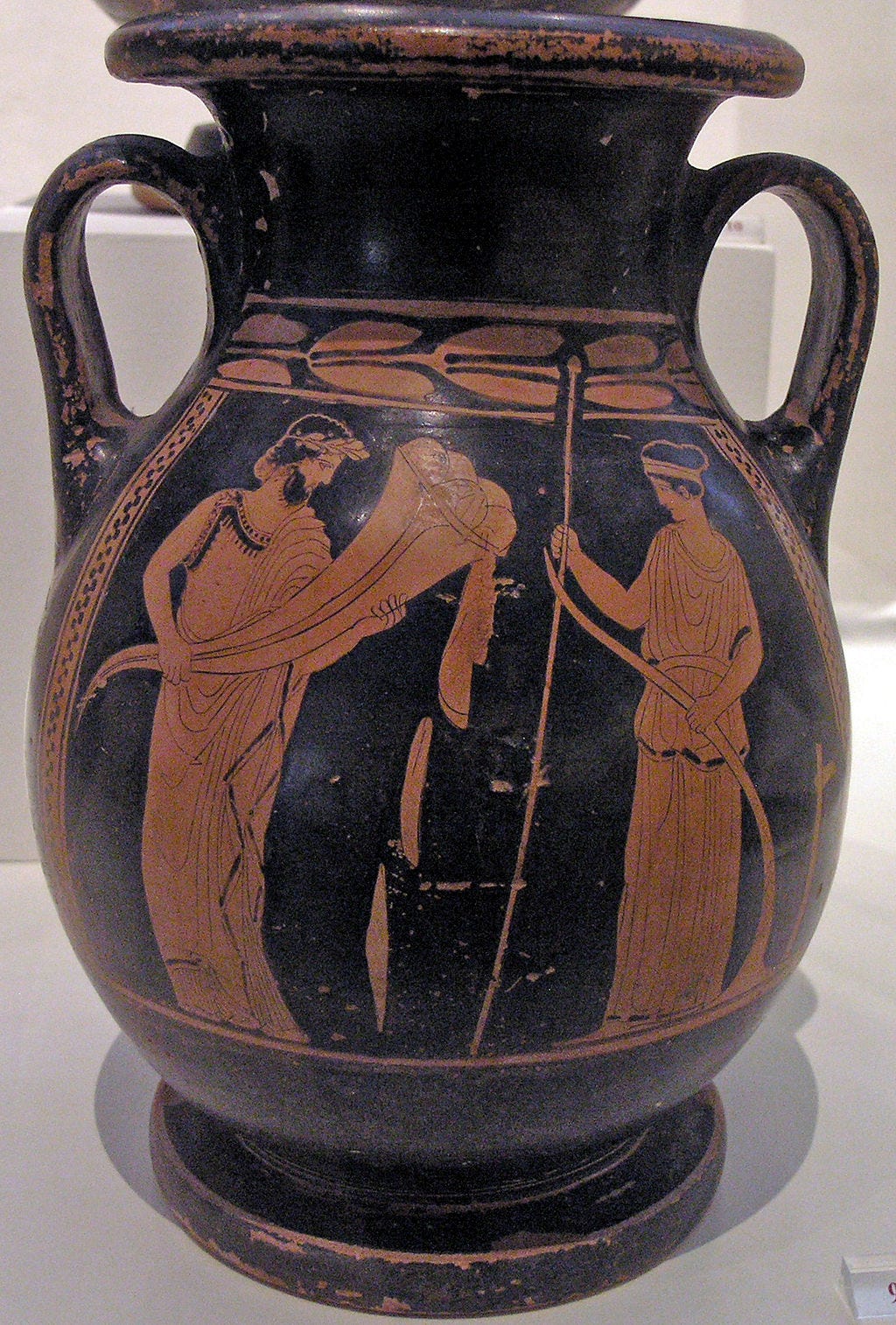

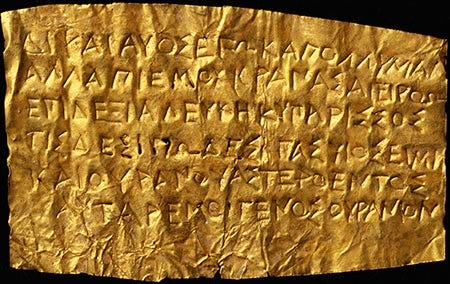

The Orphics took this trip to Hades very seriously—so seriously, in fact, that they often carried instructions with them when they were buried. These are the famous “gold lamellae” (or tablets) that are some of our oldest Orphic archaeological finds.

These gold leaves were held in the hands or mouth of the dead, and were engraved with instructions that would help the deceased’s soul navigate through Pluto’s realm— knowing which stream to stop at, which to avoid, what to say to Pluto and Persephone when they stood in front of Their Thrones, and so forth.

Most importantly, the engraved lamella reminded them of who they really were:

“I am a child of Earth and Starry Sky, and I belong to the family of the Heavens.”

By remembering who they are—kin to the Heavens, child of Earth and Starry Sky— and speaking that truth to Pluto and Persephone, the Orphic initiate gained release from the cycle of birth and death, and joined their heavenly family.

There’s so much to unpack there. We’ll examine this process in full detail another time—probably when I release my translation of the hymn to Persephone. For now, let us just note that Pluto is indiscriminate in his choice of abductees…never picky about His chariot-mates, he eventually takes us all. And that when Pluto does take us, He offers us a chance at eternal life among the stars.

And that, dear reader, is why Pluto is just as much of a Great Liberator as his fractal brother Zeus.

I’ll end it there, except to say that if you want to understand how this Orphic fractal cosmos provided the template (quite literally, the map) for Hellenistic astrological and astronomical practices, read my Translation and Commentary on the Hymn to Pluto.

Yours in Earth and Starry Sky,

✨Kristin

NOTES

*It is hard to overstate the impact that the thinking of my fellow researchers in the Oscillations anthropological study group have had on my understanding of the Orphic cosmos. I was working on the Orphic material before I met them, but in weekly collaborative reading and conversation, my understanding of the Orphic Hymns has been deepened and nuanced in ways both profound and humbling. Find our work at https://oscillations.one

**These hierarchical ways of understanding fractal correspondences can certainly be found in certain types of Late Antique, medieval, and Renaissance magic and astrology, but I would argue alongside many other scholars that attributing it to early Greek material—including Plato, Plotinus, and Iamblichus—is a fundamental misreading of their cosmology. Nobody presents the complexities of these issues in a more thorough, relatively easy-to-understand way than Earl Fontainelle in his excellent podcast The Secret History of Western Esotericism.

***Greek offerings to Underworld deities and the dead involved digging a pit in the earth, into which they poured blood, fat, and other offerings. (As opposed to sacrifices to Olympian gods, which took place on the steps of temples, with the bones and fat of animals burned on top of altars so that the smoke rose towards heaven.) This form of chthonic, or under-earthly, offering reflects the understanding that whereas the life-giving properties of Zeus and Helios stream down from above, the life-giving properties of Pluto (and other under-earth deities) push up from below.

Many earlier (and even some contemporary) scholars have used these sacrificial practices, as well as descriptions from Homer, to argue that early Greeks held a quite simplistic understanding of the underworld as simply “underground.” However, this outdated view of the early Greeks as astronomically un-savvy has pretty much been thoroughly debunked by scholars such as Alice-Amande Maravelia (Les astres dans les textes religieux en Égypte antique et dans les Hymnes Orphiques) and Alun Salt (“The Astronomical Orientation of Ancient Greek Temples,” 2009), who have shown quite convincingly that the early Greeks, and specifically the Orphics, not only had a cosmic understanding of the underworld, but that they may have even had a heliocentric understanding of the universe that they inherited from the Egyptians and subsequently refined with their own calculations.

I continue to come back to this incredible article for deeper reflection and inspiration. I seem to be learning more each time I return. Your work is a true gift for us all, Kristin. Thank you from the depths of my being.

Truly beautiful insights here Kristin! All too often we get caught up in the difference in name, Zeus/Hades, and we forget the function. When we dig into those epithets though, we see so many similarities between the different gods, it's hard not to see it as fractals. Thank you for putting this so beautifully! Love this substack!