New Translation of The Orphic Hymn of Physis (aka "Nature")

And a commentary, and an essay, and the link to Sunday's Live Chat!

Business First: Live Chat on the Hymn of Physis will be this Sunday, June 22, 2pm EDT. A recording will be available in the days afterwards. Full translation of the Hymn and link to the chat is at the end of this post.

How to Cite this Post:

Mathis, Kristin. “New Translation of The Orphic Hymn of Physis (aka ‘Nature’).” Substack newsletter. Mysteria Mundi(blog), June 20, 2025. https://mysteriamundi.substack.com/p/new-translation-of-the-orphic-hymn-f1c.

Unending, yet the End,

Incomplete, yet the Completion,

Uninitiated, yet the Initiation.

--Excerpt from the Orphic Hymn of Physis (my translation)Welcome to the weird, wonderful, and bewilderingly fractal world of Physis (pronounced “phoo-sis”), where paradox is celebrated and minds are blown!

If you’ve been reading here about the Orphics for awhile, you may have come to expect such funhouse vibes from the Orphic Hymns. But the Hymn of Physis - the longest in the entire collection - is particularly striking for its contradictions. Why?

Well, let’s start with the translation of the word physis itself. Often translated as “Nature,” the Ancient Greek word physis contains a range of meanings that are not very well captured by its English counterpart. In fact, I’d argue that translating it “Nature” is probably more obfuscating than helpful.

The English: Nature as Noun

To start, our English word “Nature” usually emphasizes materiality. Nature is an object, a thing we either exploit or a place we retreat to. It also tends to be opposed to human beings: Nature vs. Culture, or Natural vs. “Man-made.”

I won’t spend a lot of time on this overtly materialist understanding of Nature, because I’m assuming that if you’re reading this essay, you most likely have already begun questioning this view. It’s painfully obvious to most of us that a materialist, extractive view of Nature has resulted in our current ecological state of affairs of global warming, increasingly extreme weather events, and giant floating islands of trash in the oceans. (Not to mention the horrors of colonialism in all its mercantilist and capitalist forms.)

Let’s just assume, for our purposes here, that we all accept that the natural world is, in some fundamental sense, ALIVE. This isn’t too much of a stretch for many people, even those who don’t consider themselves “animists.” After all, we’re quite familiar with the idea of “Mother Nature” - whether as metaphor or a divine being. Think of the sentence, “You can pave over that field, but ultimately Mother Nature will take it back.” Whether you take “Mother Nature” literally or figuratively, the use of the phrase hints at indigenous and animist perspectives, in which Nature is someONE with whom we are in relation.

The idea of “Mother Nature” is, to some degree, an improvement over the strictly materialist view, because it gives the natural world some agency and even a sense of personality. However, whether conceived metaphorically or more literally as an actual divine being, our ideas of “Mother Nature” still tend to be framed in humanist notions of selfhood that emphasize boundaried individuality.

Like the post-Enlightenment self, “Nature” is conceptualized as a discrete, self-same identity, not a dynamic, ever-unfolding process. Sure, we might admit a certain level of “evolution” to Nature, much like we understand that a human being ages.

However, all too often, even in contemporary spiritual and animist spaces, we are taught to expect that Nature and other deities retain an essential “essence” in the same way we suppose that we ourselves retain some essential (albeit somewhat mysterious) “essence.”

Sometimes we think of this “essence” as the self, or the soul or our personality, sometimes we leave it unnamed. Almost always, it carries a lot of relatively unexamined assumptions.

In the case of the Greek gods, we learn from our earliest childhood encounters with ancient deities in storybooks and movies, that Zeus is not Aphrodite. Later on, we might be told that neither of these gods is the same as their corresponding planet. And when we later encounter deities that are clearly “natural,” like Gaia or Okeanos or Physis, it is all too easy to ascribe to them some form of the same humanist “selves” we’ve been taught apply to all deities.

It’s an understandable progression, but not terribly helpful to understanding the Greek notion of physis, nor even the traditional gods like Zeus and Aphrodite. Nor our actual cosmos, which is dynamically fractal and wildly entangled. Nor our own dynamically fractal and wildly entangled self.

So what’s the alternative?

Physis as “Characteristic Eco-pattern”

Ok ok. “Characteristic Eco-pattern” is a mouthful. And will never make it into a poem as a pleasing translation of physis. But hear me out. For those who want the brief takeaway, skip to the end of this section. But for all you nerds out there, buckle up for some deeply geeky (but hopefully fascinating) close word study.

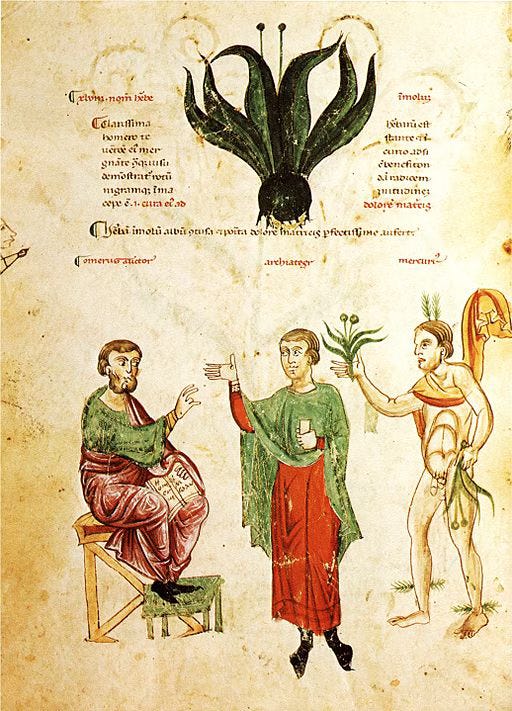

Scholars of pre-Socratic philosophy have long noted that the earliest uses of the word physis are not well-translated by the English “Nature.” The verb it is taken from (phuō) means something like “to grow” or “to sprout forth.” In Homer (Iliad 14.347), for instance, we read about how the earth made freshly sprouted (phuen) grass and flowers as a cushion for Zeus and Hera’s love-making. Or how the sorceress Kirke (aka Circe) used an herbal formula (pharmakon) to make bristles sprout (ephuse) from the heads of Odysseus’ crew-mates when she turned them into pigs (Odyssey 10.393).

Earlier in the same book, Homer used the noun physis to describe how this sprouting, growing motion can be seen as a characteristic aspect of something: what we might call its growth pattern or habit.

In a famous scene, Hermes gives Odysseus a powerful herb to counteract Kirke’s potion (pharmakon). The exact passage reads,

Saying this, Agreiphontes (i.e. Hermes) gave me the herb (pharmakon), rooting it up from the earth, and he taught me its physis. In the root it was black; the flower was like milk. The gods call it Moly. It is painfully difficult for dying males (i.e. mortal men) to dig up, but gods are capable of all things.

-Homer, Odyssey 10.303-306. My translation.

As you can see, the word physis here describes not Nature (capital N) but perhaps nature (small n): the morphology and habits of a plant, how it grows, what it looks like, what to use it for, and (presumably) how to prepare it. Its characteristics.

Pindar, a lyric poet writing in the 6th century BCE, seems to use the word similarly to describe a quality that connects humans and gods:

But in all, we bear a resemblance, either in great mind (Greek: megan noon) or in physis, to the undying ones.

-Pindar, Nemean Ode 6.4-5. My translation.

Here, Pindar is saying he’s not sure if it’s our amazing human mind or other human (presumably physical?) characteristics, but something in us is similar to the gods.

Thinking of physis this way — as describing a dynamic growth pattern or set of characteristics — is incredibly helpful when reading any of the pre-Socratic philosophers, or, for that matter, the Orphic Hymns.

The key here is that physis doesn’t describe a single fixed characteristic or identity (like a leaf morphology that can be captured on an illustrated page). Rather, physis describes a dynamic, fluctuating set of (entangled) habitual growth patterns that include, to some degree, its surrounding ecosystem.

Every gardener intuitively knows this pre-Socratic meaning of physis. In plants, each individual specimen will be different, but there will be something (its physis) - a combination of form, growth pattern, habit, locale, uses, methods of harvesting, etc. etc. - that allows you to say, “That is chamomile.” You will be able to recognize chamomile even if its appearance has changed (for instance when it is dried or pulverized), because the physis of chamomile not only encompasses its cute flowers and characteristic leaf, but also the fact that it is sweet, has a fragrance, and tends to calm your stomach and make you a little sleepy.

Chamomile’s physis also stretches slightly beyond the physical bounds of the plant itself in that to understand its physis would entail learning about the various soils, climates, and moisture levels it prefers, as well as the critters (both beneficial and pests) with which it cohabitates.

The physis of chamomile even extends into the realm of the human, because to know its physis properly, one needs to think about very human activities, such as harvesting and preparation - which include knowledge of the seasons (which in turn, in Ancient Greece would entail looking at the stars), as well as a knowledge of either cookery or the preparation of herbal remedies. (And perhaps even star lore.)

I’m sure you can think of even further examples of how the physis of chamomile is entangled with all manner of other realms, be they plant, animal, mineral, and even human and astral.

It’s easy to see once we think about it in a different way, but there is simply no good word (or even phrase) for it in English. “Characteristic Eco-Pattern” is as close as I’ve been able to get, though I’ve also tried out “Dynamic Life-Pattern,” (which maybe makes it sound like someone’s New Age-y ritual practice) and even “Dynamic Pattern of Assemblage,” (where “Assemblage” is used in the way philosopher Bayo Akomolafe has described it). But although I find Bayo’s use of “assemblage” super useful to my own thinking, I ultimately discarded it in the Ancient Greek context because it sounded a little too mechanical, like something out of a 90s cyberpunk novel.

Orphic Physis

So where does that leave us with the Orphic Hymn of Physis?

Well, I’d say it’s no accident that we are having trouble grasping the essential quality of physis, because that very inability to pin it down as “this” or “that” is intrinsic to physis itself. If you look for it, you quickly wind up with its opposite. Which tends to break one’s mind into a state of what the Greeks called aporia, a state of perplexity or being lost.

Pre-Socratics like Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Zeno (and even the historical Socrates himself) valued this state as being the only way to grasp the ungraspable. They saw aporia as a state of knowing/unknowing that exceeds the boundaries of intellect, because it requires us to hold two opposing ideas at once. Which is precisely a defining characteristic of “the All.”

Or perhaps it’s better to say that by not grasping the ungraspable, both the idea of “we” and “it” and even of “grasping” itself are dissolved. Dwelling beyond the limits of being and non-being, we encounter the All.

I’m tempted to leave it there and get to the hymn itself, but I want to take one more stab at defining physis, with what I think is more of a “vibe check” than a hard and fast definition:

Physis is a process, an unfolding, an engendering creative characteristic eco-pattern; while it encompasses death, existing as it does beyond dualities, it always trends towards the production of more life.

Phew! I definitely prefer aporia to crafting definitions like that.

Go ahead, read the hymn itself, and tell me what you think. I love reading your comments and hearing your thoughts in the Live Chat, so go for it!

✨✨ Kristin

p.s. Scroll to the very bottom for the Live Chat link!